When you're 16, things tend to sink in deep and stay there for life. It's hard for me to be objective about the music I obsessed over back then, for example: it hit me hard and left impacts like craters, Over time the dust and ash settles; now they're just part of the inner landscape, overgrown but always visible.

And not just music. It's October 1989, and we're on a family holiday on Arran. I've a new, burgeoning obsession: mountains. Somewhere in the last couple of years I've shifted from being an often reluctant hanger-on trailing after my dad in soggy home-knit pullovers and hand-me-down plus fours, a sort of unspoken apprenticeship. Something has come to fruition, a tipping point has been reached. Maybe it's age, an accrual of confidence, a first secure foothold in the arts of map and compass, whatever - but now I

want more than anything to get out there into the hills, alone or with others, it doesn't matter. Oh and there's this list of mountains called Munros.

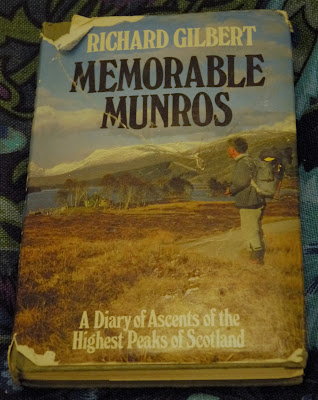

So, back to Arran. We're in a bookshop and after scanning the outdoors shelves I come away with a little volume called 'Memorable Munros' by Richard Gilbert. Sitting in the back of the car, I start devouring it straight away. It hits me hard and leaves a crater. It turns out to be one of the most inspiring outdoors books I'll ever read, and it's stayed with me for life.

|

| Monadh Liath, 1989 |

'Memorable Munros' is no literary work, it's not a piece of 'fine writing' about nature and mountains and whatever could it all mean. There is no philosophising, and little rhapsodising. It delivers what it says on the cover: a diary of ascents of the highest peaks in Scotland. It's arranged by geographical area from north to south, so there's no linear narrative structure. Entries are generally short, sparse and functional. And yet it works.

|

| Braeriach, 1990 |

What I took from 'Memorable Munros' was an

attitude underpinning the writing. The author is out there in all weathers, all seasons, alone or with friends or leading school groups, sometimes even at night. Behind the words is an unspoken but unmistakeable weight of experience; you can sense the blend of resilience, self-reliance and adventurousness tempered with caution and wisdom, all those elements we try to balance when we go into the mountains. The entries were written up at the time, often in the tent or the bothy, so those plain words have a rough immediacy, unfiltered, like the ink is barely dry.

|

| Braeriach again, 1994 |

Above all, there is joy - the simple, powerful, understated joy of being in wild places. There is a vivid account of a March backpacking trip around the mountains of Loch Mullardoch in 1962: a tale of snowstorms, freezing high camps, Vat 69 whisky and pipe smoke. Another entry tells of climbing Ben More on Mull, a huge, complicated round trip taken by the author and his brother for a fleeting but perfect winter day on the mountain. 'Memorable Munros' contains some hair-raising 'epics' but these are never boastful, never over-egged. He takes the rough with the smooth in the mountains, with the minimum of fuss.

|

| Ben Vorlich (Loch Lomond), 1995 |

Richard Gilbert passed away in January this year. As is often the way, I learned a whole lot more detail about him after his passing, from obituaries and reminiscences from other outdoors figures. He was, perhaps unsurprisingly, deeply alarmed at the destruction of wild land and was involved in trying to stop it. He was a teacher by profession, teaching chemistry in the classroom, and mountaincraft outside, leading parties of schoolboys on expeditions in the Highlands and abroad that even now (maybe especially now) seem hugely ambitious. It would seem his personal joy in the hills was matched by his desire to share it with others, and preserve it for others.

And that, perhaps, is why 'Memorable Munros' had such an effect on me. It showed me that great adventures were accessible; that human, not superhuman, qualities were needed. All this whilst never glossing over the dangers and difficulties or 'dumbing down' the hills to our level or pretending risk can be obliterated. 'A Diary of Ascents of the Highest Peaks in Scotland' - maybe that doesn't quite cover it after all.

Young Explorers Trust: Richard Gilbert obituary |

| The Fara above Dalwhinnie, 2000 |

Comments

Post a Comment