The wilderness is closer than you think

We spent the first week and a half of May in Scotland, although it felt more like March. Hamish Brown in Hamish's Groats-End Walk talks about the 'peewit storms' - a long-observed propensity for cold and snowy weather to occur in the Highlands in early May. I climbed Glas Tulaichean and Carn an Righ in sleet and snow on 5th May last year, and driving north to Dornoch on 3rd May this year we encountered snow on Slochd summit and a fresh coat of white on the higher hills.

Overall the poor start to the summer has reminded me of the reality of long-distance backpacking: there are days of bad weather to be endured as well as good weather to be savoured. On those bad days there's usually nothing for it but to accept the discomfort of being wet and cold, and get on with it. If the Tay watershed walk is to be a success I'll need to have some resilience and mental fortitude to cope with days of walking and wild camping in bad weather. I was well tested in that regard this week.

The original idea had been to make a three day trip to the Fisherfield Forest and meet some friends there. However the planned day of departure (Saturday 4th May) brought upland gales, heavy rain and snow on the tops - it was just too wild to go. With only two days to play with now, I changed plans completely: the weather outlook was still poor but the far north of Sutherland looked like it might escape the worst. So it was off to the Foinaven group for an overnight trip. Despite wind, rain and a wet camp in the vast elemental ampitheatre between Foinaven and Arkle, I reached the summits of these two peaks and nearby Meall Horn.

Ascending Foinaven in particular was unforgettable. What would be an entertaining scramble on a calm day assumed epic proportions as I crawled and staggered up the shattered ridge, with little visibility. I struggled to plant solid footsteps on sharp, shifting rocks whilst fighting to keep my balance in the wind. The right (or wrong) gust could have pitched me into the void of one of the mountain's eastern corries.

In retrospect I loved it. What especially sharpened the experience was the creeping sense that I was very far from any roads or houses. I was doubly isolated - by cloud in my own little cell of visibility, and then by exhausting miles of scree, bog, rock and unpredictable burn crossings. I had a strong feeling of being thrown back on my own resources. I met no-one else on the mountain. There's nothing like being out in a place like this in bad weather to remind you that the world is essentially wild, as in self-willed ('wild' and 'will' share the same etymological roots), working to its own rules, its own agenda. If you don't respect that, you can expect to run into trouble.

I've been reading a bit lately about concepts of wildness and wilderness (or 'wild land' as it is termed by officialdom in Scotland)*, and got interested in thinking about and contrasting my Foinaven trip with two enjoyable walks I did later in the week - over Ben Venue in the Trossachs, and a round of the Cliesh Hills near my parent's home. The definition of wilderness is hard to pin down as it can be so subjective, but commonly it is used to refer to areas that do not bear the mark of modern civilisation: no roads, no industrial development, no habitation. Instead, these are areas that are left to their own - or nature's - devices. Most people, when they think of wilderness, will automatically think on a grand scale - soaring mountains, empty moors, deep forests, pristine lakes and clear, rushing rivers. The American or Canadian idea. Foinaven and its surrounds come about as close to this as you can get in these islands. Or so I thought until I stumbled over a moss-covered old tree stump near Loch an Easain Uaine. Far from being in a natural state, these moors are denuded and suppressed by centuries of human activities and 'management' for sport.

Ben Venue however is right on the southern edge of the Highlands and in easy reach of Glasgow and Stirling. Despite wet and windy weather again, it was a joyful carefree meander in a lushly upholstered and relatively small-scale environment after the drama and austerity of Foinaven and its bare miles. Whilst Foinaven threw me back on myself, Ben Venue drew me outwards: the smell of damp earth and new growth and sound of birds in the lower forests, red deer hinds flowing smoothly over a hillside of felled plantation, a family of feral goats in Gleann Riabhach, the steady drift of grey skirts of cloud across the hillsides.

A couple of days after that we were over in Fife and I went for a short walk through the Cliesh Hills. This miniature range was created by ancient volcanic activity. It is on the cusp of an industrialised landscape: you see Mossmorran and Grangemouth from its heights. However look the other way and you see the grassy ramparts of the Ochils. Sadly this view is no longer what is was, marred now by wind turbines sprouting above Glen Devon. West beyond the Wallace Monument are the faint shapes of the first Highland peaks - Ben Ledi, Ben Vorlich, Ben Lomond. North-east you might get a distant glimpse, as I did today, of the snow-streaked Mounth.

Since I was five or six years old I have been visiting these hills, in all weathers, all seasons, in the dark of autumn and winter evenings and in the height of summer. I've fished for perch and pike in the hill lochs with my Dad and sister, scrambled on the little cliffs and crags in summer, and sledged in the winter. Objectively these hills are nothing special, they are not particularly scenic, but my relationship with them has been one of engagement rather than detached admiration. They are part of my geography. I'm sure most people have a place like this.

The Cliesh Hills are tiny in scale and bear many marks of human wear. What is not blanketed in forestry is cropped by sheep.The highest point, Dumglow (379m), was once crowned by a Neolithic fort. A plaque in the cairn commemorates a shepherd who worked the hills in the 1930s and 1940s. Ruined farms stand in the forest at Kings Seat, and on a dry rise above Tipperton Moss. Loch Glow is dammed at one end and busy with anglers throughout the summer. It hardly qualifies as wilderness, in any pure or grand sense of the word.

However in deep winter, outside the fishing season, when snow lies deep, the little hill lochs are frozen and waves of wind-blown powdery snow snake and skitter across the ice, when the sun sets and the stars shine out, when the geese call as they come in to roost on Loch Glow, and a fox crosses the hillside on its own business - you are in the wild, and you are not the measure of all things.

*Chris Townsend recently republished an interesting article in which he discussed the difficulty in trying to draw sharp distinctions between wild land and non-wild land, as SNH and the Scottish Government seem to be engaged in with their latest wild land mapping exercise.

Other good recent reads have included Robert Macfarlane's The Wild Places, and Into The Wild by Jon Krakauer, a fascinating account of young Chris McCandless who perished in the Alaskan outback in the summer of 1992.

Overall the poor start to the summer has reminded me of the reality of long-distance backpacking: there are days of bad weather to be endured as well as good weather to be savoured. On those bad days there's usually nothing for it but to accept the discomfort of being wet and cold, and get on with it. If the Tay watershed walk is to be a success I'll need to have some resilience and mental fortitude to cope with days of walking and wild camping in bad weather. I was well tested in that regard this week.

The original idea had been to make a three day trip to the Fisherfield Forest and meet some friends there. However the planned day of departure (Saturday 4th May) brought upland gales, heavy rain and snow on the tops - it was just too wild to go. With only two days to play with now, I changed plans completely: the weather outlook was still poor but the far north of Sutherland looked like it might escape the worst. So it was off to the Foinaven group for an overnight trip. Despite wind, rain and a wet camp in the vast elemental ampitheatre between Foinaven and Arkle, I reached the summits of these two peaks and nearby Meall Horn.

Ascending Foinaven in particular was unforgettable. What would be an entertaining scramble on a calm day assumed epic proportions as I crawled and staggered up the shattered ridge, with little visibility. I struggled to plant solid footsteps on sharp, shifting rocks whilst fighting to keep my balance in the wind. The right (or wrong) gust could have pitched me into the void of one of the mountain's eastern corries.

In retrospect I loved it. What especially sharpened the experience was the creeping sense that I was very far from any roads or houses. I was doubly isolated - by cloud in my own little cell of visibility, and then by exhausting miles of scree, bog, rock and unpredictable burn crossings. I had a strong feeling of being thrown back on my own resources. I met no-one else on the mountain. There's nothing like being out in a place like this in bad weather to remind you that the world is essentially wild, as in self-willed ('wild' and 'will' share the same etymological roots), working to its own rules, its own agenda. If you don't respect that, you can expect to run into trouble.

|

| Waterfall in Gleann Riabhach |

|

| Sput Ban, Ben Venue |

A couple of days after that we were over in Fife and I went for a short walk through the Cliesh Hills. This miniature range was created by ancient volcanic activity. It is on the cusp of an industrialised landscape: you see Mossmorran and Grangemouth from its heights. However look the other way and you see the grassy ramparts of the Ochils. Sadly this view is no longer what is was, marred now by wind turbines sprouting above Glen Devon. West beyond the Wallace Monument are the faint shapes of the first Highland peaks - Ben Ledi, Ben Vorlich, Ben Lomond. North-east you might get a distant glimpse, as I did today, of the snow-streaked Mounth.

Since I was five or six years old I have been visiting these hills, in all weathers, all seasons, in the dark of autumn and winter evenings and in the height of summer. I've fished for perch and pike in the hill lochs with my Dad and sister, scrambled on the little cliffs and crags in summer, and sledged in the winter. Objectively these hills are nothing special, they are not particularly scenic, but my relationship with them has been one of engagement rather than detached admiration. They are part of my geography. I'm sure most people have a place like this.

The Cliesh Hills are tiny in scale and bear many marks of human wear. What is not blanketed in forestry is cropped by sheep.The highest point, Dumglow (379m), was once crowned by a Neolithic fort. A plaque in the cairn commemorates a shepherd who worked the hills in the 1930s and 1940s. Ruined farms stand in the forest at Kings Seat, and on a dry rise above Tipperton Moss. Loch Glow is dammed at one end and busy with anglers throughout the summer. It hardly qualifies as wilderness, in any pure or grand sense of the word.

However in deep winter, outside the fishing season, when snow lies deep, the little hill lochs are frozen and waves of wind-blown powdery snow snake and skitter across the ice, when the sun sets and the stars shine out, when the geese call as they come in to roost on Loch Glow, and a fox crosses the hillside on its own business - you are in the wild, and you are not the measure of all things.

|

| Gleann Riabhach |

*Chris Townsend recently republished an interesting article in which he discussed the difficulty in trying to draw sharp distinctions between wild land and non-wild land, as SNH and the Scottish Government seem to be engaged in with their latest wild land mapping exercise.

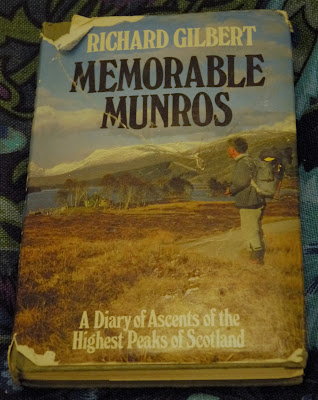

Other good recent reads have included Robert Macfarlane's The Wild Places, and Into The Wild by Jon Krakauer, a fascinating account of young Chris McCandless who perished in the Alaskan outback in the summer of 1992.

Comments

Post a Comment