Walking and learning

Walking 300 miles through mountains and lowlands was a new experience for me. I'd never travelled so far on foot or been outdoors so long. I'm not sure I learned anything completely new, but that's not to say I didn't end up any wiser. It's one thing to be told something (however often), another to work it out for yourself first-hand, when your well-being depends on it. So, here are a few insights, lessons, and things I came to understand a little better during the walk.

Walking 300 miles through mountains and lowlands was a new experience for me. I'd never travelled so far on foot or been outdoors so long. I'm not sure I learned anything completely new, but that's not to say I didn't end up any wiser. It's one thing to be told something (however often), another to work it out for yourself first-hand, when your well-being depends on it. So, here are a few insights, lessons, and things I came to understand a little better during the walk. 1. You can't force the pace

At least, not too much. The weather and the landscape are going to do their own thing. They don't care about what you think you need. Then you realise that you're only flesh and blood too: another part of nature. Some days are wet, miserable, hard going. Other days may be not so onerous but you're just not quite so up for it, the energy isn't there, you feel lethargic; or you may be feeling it from a big day previously. I got better at tuning in to myself and my surroundings, knowing when to cut my losses and ease up, stop early.

Of course there were also days of fair weather and endless evening fade-outs, uplifting days when feet seemed to have wings and the land was a frozen symphony of light and texture, depth and distance, glorious and all-encompassing. On those days it could be hard to stop! I remember especially the walk from Balquhidder Station to Stuc a'Chroin. A hot sunny afternoon segued into a magnificent late evening as I walked the ridge from Beinn Each to the Stuc. The lowering sun mixed it up with ever-evolving banks of low misty cloud to dazzling - and achingly soft - effect. It was nearly dark by the time I got the Trailstar up, by Lochan a'Chroin.

Of course there were also days of fair weather and endless evening fade-outs, uplifting days when feet seemed to have wings and the land was a frozen symphony of light and texture, depth and distance, glorious and all-encompassing. On those days it could be hard to stop! I remember especially the walk from Balquhidder Station to Stuc a'Chroin. A hot sunny afternoon segued into a magnificent late evening as I walked the ridge from Beinn Each to the Stuc. The lowering sun mixed it up with ever-evolving banks of low misty cloud to dazzling - and achingly soft - effect. It was nearly dark by the time I got the Trailstar up, by Lochan a'Chroin.A bit of patience and resilience goes a long way. Keep your shape, and remember that it has to stop raining and blowing eventually.

2. Human-friendly route planning

You need to allow for the unexpected, and for things like bad weather that are expected but unpredictable. I didn't build in enough leeway. In the wildest parts of the walk, from the Cairnwell through to Tyndrum, the daily distances I planned out were too much, over a lot of merciless terrain. I needed a couple of extra 'wild card' days built in to this part of the walk, and a rest day at Kingshouse might have enabled me to recuperate enough to take on the Black Mount.

|

| Cruach Ardrain |

Compromising on the original idea of walking the exact watershed all the way was disappointing, but I ended up with a route that was right for me, I think. The Black Mount traverse - it was a shame to miss that, though.

3. How freedom works

Here it starts to get curiously contradictory. I remember a few years ago meeting a musician who made his living travelling Europe in a motor home, gigging and recording wherever the work came up. He'd made a conscious decision not to become embroiled in the world of salaried careers, mortgages, and chasing after dead things.

The first thing that struck me was of course the extraordinary amount of freedom he'd engineered for himself. The second thing was the discipline and single-mindedness needed to achieve and maintain it. This really challenged the lazy conventional notions of what 'dropping out' means, that I had in the back of my mind along with all the other acquired baggage. It's not about lying back and going with the flow, which in fact is more likely to result in drifting into un-freedom (if that's a word). Quite the opposite: it takes determination, self-belief, and an ability to let other people's furrow-browed looks bounce off you. It's all the more difficult in a society that touts itself as free but becomes ever more bland and conformist, regulated and controlled, and mentally dis-eased.

Anyway, that's becoming a rant; back to the walk. Yes, it was freedom. Essentially I dropped out for five weeks, but it wasn't a doss. It was hard work, but it was self-directed work. The good sort, towards self-chosen goals. Without the goals, the freedom is only half-realised.

4. How adventure works

4. How adventure worksIt occurred to me that there's a contradiction at the heart of adventure too. It's both a commitment and a relinquishing, a letting go. Head outside and keep walking, and who knows what will happen, what you'll see and who you'll meet. In committing to the walk I was letting go of something else - predictability, control. There were risks but the rewards were worth it. Committing to a future goal and living in the moment.

5. The futility of 'all or nothing' thinking

As I said, my route didn't work out as expected. I'd wanted to walk the exact watershed all the way, so in that sense the venture was a failure. Except it didn't feel that way. At no point did I seriously consider giving up when I was forced off the watershed.

It's a curious and common human quirk to think that just because you can't do everything, you might as well do nothing. But something is always better than nothing. By the time I had to compromise on the route I was so entranced by the walk, it didn't bother me so much. I worked out pretty quickly, in fact, that the route was secondary, a means to the end of experiencing a big trek and an extended time outdoors.

6. What really matters about being outside

Challenges, firsts, bagging, conquering... Nature is so often just a backdrop onto which we project ourselves and an adventure theme park in which we prove ourselves, rather than something we belong to and are part of. Our perceived separateness from and superiority to nature is implicit in this. It's an old notion that's fraying at the edges and will continue to do so as we continue to dump the cost of our excesses on the environment, but it's still far from dead.

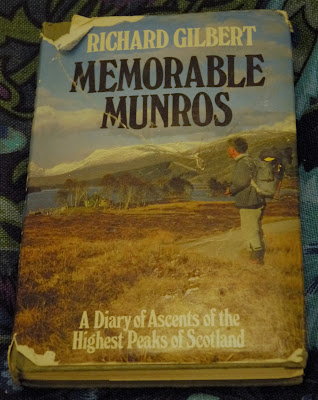

Challenges, firsts, bagging, conquering... Nature is so often just a backdrop onto which we project ourselves and an adventure theme park in which we prove ourselves, rather than something we belong to and are part of. Our perceived separateness from and superiority to nature is implicit in this. It's an old notion that's fraying at the edges and will continue to do so as we continue to dump the cost of our excesses on the environment, but it's still far from dead.Before I went on this walk I was already moving away from the peak bagging mentality. It's a funny game, the Munros. The land is carved up like a Risk board into 'sections' each with a list of peaks to be bagged (sacked?). It's a curiously colonial mindset to bring to the free-flowing and boundless glories of nature and landscape.

The first night of the walk was enough to for me realise what it was all about. Camped in the woods, I lay awake for a long time in the darkness as the night came alive around me with snuffling, shuffling, and rustling, the hooting of an owl and thump of deer hooves. I experienced something bigger than me, bigger than us. We walk a thin crust over an ancient flow that's always calling us back. Being outside is simply its own reward. It's where the real life is.

I walked the Tay catchment boundary for two great charities, Scottish Wild Land Group and Venture Trust.

You can still sponsor me by making a donation to Scottish Wild Land Group here: https://mydonate.bt.com/

and Venture Trust here: https://mydonate.bt.com/

Comments

Post a Comment