A walk in the park

We started and finished in the fleshpots. Three days and two nights from Callander to Inversnaid on Loch Lomond. In between, it got wild, lonely, and quiet, another side of the national park, far from rangers and permits and interpretation boards and visitor management and bureaucracy. Instead there were the sparse cries of ravens, yellow grasses bowing in the autumn winds, tussocks and bogs and peat hags. The SMC's guidebook for the Southern Highlands describes the uplands between popular Ben Ledi and Stob a'Choin, our final summit as '...a rather desolate stretch of featureless hills of no great interest to the climber or walker.' It didn't disappoint!

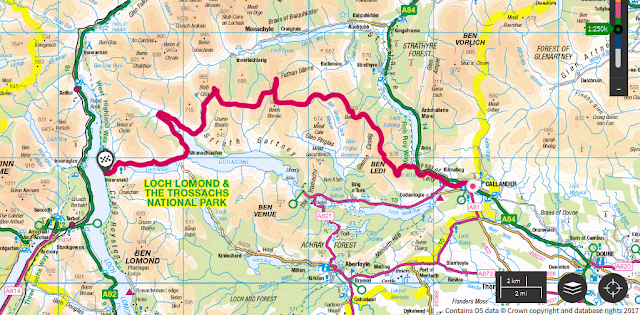

Here's the route, minus my little pre-dawn excursion from the second camp to Stob a'Choin's summit. Around 50 kilometres walked and over 2,500 metres climbed in all:

We also left the motors at home. Instead, trains to Stirling where we rendezvoused, bus to Callander, then boat from Inversnaid to Tarbet at the other end and a bus south to Glasgow then, for me, a train to Edinburgh.

Day one took us along the course of the old railway from Callander to Balquhidder, where the wispy seeds of the rosebay willowherb frayed and scattered. The Highlands begin abruptly here as the path climbs into native oakwood, the valley sides steepen, and the voice of the river on the right rises from a murmur to a roar. Ben Ledi sheltered us until the final summit where we caught the full force of a restless, portentous northerly. We walked on into the wind, into the hills. The light was low and sombre; here and there the bellies of the clouds brushed the hilltops and smeared the air with rainbows and showers.

We camped beyond Benvane where an old right-of-way, clearly little used now, drops north on its way from Brig o'Turk to Balquhidder. We found fine grassy pitches near the confluence of two lively burns, amongst stands of dense, dying bracken. Birch and rowan clung to the steepest of the slopes, safe from the nibblings of sheep and deer. There was a glimpse of alpenglow on the hilltops to the north, but dusk seemed to come early under dark and weighty clouds. The wind dropped away after dark. An old, healed fire ring, green grass in a circle of stones, seemed to magnify the loneliness.

We chatted in the tarp for a bit over hot drinks (a teetotal trip this one, having both forgotten the usual whisky), then turned in early.

Ten hours' sleep put away a week of work, worries, rushed packing, a late night and an early start. The morning brought more cloud, and a hovering kestrel nearby. The early blue soon hazed over and fog drifted across the hillsides, presaging rain. In the end we caught just a few spitting showers. Again that restless wind. Our route lay across a succession of trackless boggy ridges that felt very far from anywhere, though it seemed we were never far from a raven. Beinn Stacach, the highest point of this tract of moorland, lay north out on a limb. We found shelter behind an outcrop, dumped the bags, and walked out and back. Returning to the outcrop for lunch we startled a big fox which charged off over the skyline holding its huge brush straight out behind it - so much bigger and more impressive than its urban cousins.

After a brew and lunch, there was more of the same terrain. The Crianlarich mountains were drawing closer, familiar yet strange from this nameless empty quarter, probably a view that's not often seen. If we hadn't been linking together mountains that shouldn't be linked together, Mick observed, we would never have seen this either.

All afternoon the great knobbly bulk of Stob a'Choin grew slowly ahead of us, whilst the trackless terrain of bogs and tussocks, ups and downs gobbled up the hours. The ground around this mountain is hugely complex with knolls, outcrops, cliffs, gullies and sheltered hollows. Streams rise very high on the hill and its southern upper slopes are seamed with burns and trickles. We followed one up to the ridge and the summit - only to find the real summit was a further mile west over a very convoluted, warty ridge. An embarrassing failure to fully absorb the map from me, but one of the best views he'd ever seen according to Mick, and I wouldn't argue with that.

It was too late to get to the top now. We dropped south as the clouds broke up further, giving way to long shadows and dazzling golden light. Mick spotted a dryish looking knoll and we camped still high with a long view down to Loch Katrine.The skies cleared fully; darkness crept up from Strath Gartney to the south, chasing the golden evening glow up the slopes behind us to a last stand on the crags and gullies around the summit of Stob a'Choin. Then night, and a sky full of stars.

The mobile phone alarm jolted me awake. I scrabbled in the dark, disorientating confines of the bivvy bag to locate and switch it off. 5.30am, still dark. I dozed on for another 45 minutes and the beginnings of grey dawn, then wrenched myself out of my warm cocoon and into wet socks, neoprene socks and trail shoes. After a hurried miso soup and a buttery (fusion cuisine, backpacking style!) I climbed towards Stob a'Choin. Venus and a sliver of moon hung just above the shoulder to my right as I set off. Soon I was amongst the complex gullies, crags and streams, picking a way through, using hands sometimes. I emerged near the summit as the sun rose out of a bank of low cloud to the east and painted the hilltops. The Crianlarich hills were close and huge and brutal-looking to the north, Stob Binnein especially impressive, drawing up its bulk from the glen floor, above broad skirts seamed with gullies and crusted with outcrops, to a fine complex of sweeping ridges. Cloud came and went from its summit.

I touched the tiny cairn then wavered for a few minutes wondering whether I should visit another little top a couple of hundred metres north west 'just in case'. But in the end I turned and jogged downhill; I'd told Mick I'd be back by 8 and we had a boat to catch later on.

The day's next act was the hardest, especially for bodies already tired by a day and a half of trackless bog and moorland. We picked up where we left off, descending to the glen where the tightly meandering Allt a'Choin flowed generally south to Loch Katrine. The glen floor was sodden and vegetated, trackless of course. We started to get a feel for reading the vegetation, where we might expect ankle-sucking bog or drier going.

I felt ropy with fatigue and hunger after my dawn climb. Deer fences closed in on either side of the burn sheltering trees recently planted as part of the Great Trossachs Forest project. I made an ill-thought-through attempt to cross the burn over a natural weir of slimy boulders towards a gate in the fence on the far side and nearly fell in. I had enough insight to realise I wasn't thinking straight, and drew back. In the end, the two deer fences never met and we made it down to the road by Loch Katrine following a well established deer trod through the bracken and head-high birch scrub, clearly a well-used corridor for the animals to reach the shelter of the loch side woods from the high ground..

The deer fences were controversial when they first went up to protect the new plantings. It seems the migratory paths from upland to valley shelter were disrupted, trapping the animals above the treeline in harsh weather. It's hard to know what the answer is. Perhaps it's an example of failing to tackle a problem head on, a modern tendency to avoid difficult choices and favour complex workarounds with unintended (and in this case, arguably cruel) consequences - to try to change everything while changing nothing. Think electric cars or biofuels or geoengineering to combat climate change. Would a serious reduction in deer numbers via culling to a level where deer fences are not needed, actually be more humane? One thing is for sure, deer belong in the Highlands, they're magnificent animals well attuned to their environment. Watch a red deer take minutes to cross the hillside you've spent the best part of an hour toiling across. I hope very much we don't start to think of red deer as 'vermin', rats with antlers.

A tarmac road runs along the north shore of Loch Katrine and round to Stronachlachar on the south side. It was a shock to be back suddenly in daytripper land straight from some of the loneliest hill country in the southern Highlands. A steady trickle of bikes passed us as we plodded along in silence, both wrapped up in fatigue. We passed the old Clan Gregor burial ground on a promontary in the loch, and Glengyle House, birthplace of Rob Roy. There used to be a village in upper Glen Gyle. Now the Beauly-Denny pylons march down the glen, and the massive service road. It must have been a lovely place once, where the glen tapers away to the horizon from the head of the loch. Now it's industrial and off-putting.

The original plan had been to strike uphill to Beinn a'Choin from here, taking a direct cross-country route to Loch Lomond, but more deer fences stretched across the hillside. That was enough to put us off. We walked on to Stronachlachar for lunch by the pier where the steamer calls in the summer. A dustbin lorry pulled up containing two very bored refuse collectors spending the day travelling long distances along narrow roads to empty a small number of bins. We could relax a bit now as we only had a few easy miles to Inversnaid. After a leisurely lunch and much refreshed we picked up the Great Trossachs Path heading west above Loch Arklet. This section was a surprising gem. The trail follows the line of the old military road to Inversnaid Garrison, well above the public road, through patchy woods. The Arrochar Alps filled the view ahead. On the right, the slopes up to Beinn a'Choin are open and accessible here, noted for next time.

Before long we were winding through the oakwoods down to Loch Lomond, and I was thinking how great it was to see and approach it from a new angle, and be reminded that there's a good reason for all the fuss and popularity. We fell off the teetotal wagon with pints outside the Inversnaid Hotel, waiting for the waterbus to Tarbet. We'd made it easy on ourselves on this trip, and also difficult. It was a hard one to sum up. "Here's to another... victory" said Mick hesitatingly as we clinked pints. When you link up mountains that shouldn't be linked up, strange and wonderful things happen.

Here's the route, minus my little pre-dawn excursion from the second camp to Stob a'Choin's summit. Around 50 kilometres walked and over 2,500 metres climbed in all:

We also left the motors at home. Instead, trains to Stirling where we rendezvoused, bus to Callander, then boat from Inversnaid to Tarbet at the other end and a bus south to Glasgow then, for me, a train to Edinburgh.

Day one took us along the course of the old railway from Callander to Balquhidder, where the wispy seeds of the rosebay willowherb frayed and scattered. The Highlands begin abruptly here as the path climbs into native oakwood, the valley sides steepen, and the voice of the river on the right rises from a murmur to a roar. Ben Ledi sheltered us until the final summit where we caught the full force of a restless, portentous northerly. We walked on into the wind, into the hills. The light was low and sombre; here and there the bellies of the clouds brushed the hilltops and smeared the air with rainbows and showers.

We camped beyond Benvane where an old right-of-way, clearly little used now, drops north on its way from Brig o'Turk to Balquhidder. We found fine grassy pitches near the confluence of two lively burns, amongst stands of dense, dying bracken. Birch and rowan clung to the steepest of the slopes, safe from the nibblings of sheep and deer. There was a glimpse of alpenglow on the hilltops to the north, but dusk seemed to come early under dark and weighty clouds. The wind dropped away after dark. An old, healed fire ring, green grass in a circle of stones, seemed to magnify the loneliness.

We chatted in the tarp for a bit over hot drinks (a teetotal trip this one, having both forgotten the usual whisky), then turned in early.

Ten hours' sleep put away a week of work, worries, rushed packing, a late night and an early start. The morning brought more cloud, and a hovering kestrel nearby. The early blue soon hazed over and fog drifted across the hillsides, presaging rain. In the end we caught just a few spitting showers. Again that restless wind. Our route lay across a succession of trackless boggy ridges that felt very far from anywhere, though it seemed we were never far from a raven. Beinn Stacach, the highest point of this tract of moorland, lay north out on a limb. We found shelter behind an outcrop, dumped the bags, and walked out and back. Returning to the outcrop for lunch we startled a big fox which charged off over the skyline holding its huge brush straight out behind it - so much bigger and more impressive than its urban cousins.

After a brew and lunch, there was more of the same terrain. The Crianlarich mountains were drawing closer, familiar yet strange from this nameless empty quarter, probably a view that's not often seen. If we hadn't been linking together mountains that shouldn't be linked together, Mick observed, we would never have seen this either.

All afternoon the great knobbly bulk of Stob a'Choin grew slowly ahead of us, whilst the trackless terrain of bogs and tussocks, ups and downs gobbled up the hours. The ground around this mountain is hugely complex with knolls, outcrops, cliffs, gullies and sheltered hollows. Streams rise very high on the hill and its southern upper slopes are seamed with burns and trickles. We followed one up to the ridge and the summit - only to find the real summit was a further mile west over a very convoluted, warty ridge. An embarrassing failure to fully absorb the map from me, but one of the best views he'd ever seen according to Mick, and I wouldn't argue with that.

It was too late to get to the top now. We dropped south as the clouds broke up further, giving way to long shadows and dazzling golden light. Mick spotted a dryish looking knoll and we camped still high with a long view down to Loch Katrine.The skies cleared fully; darkness crept up from Strath Gartney to the south, chasing the golden evening glow up the slopes behind us to a last stand on the crags and gullies around the summit of Stob a'Choin. Then night, and a sky full of stars.

The mobile phone alarm jolted me awake. I scrabbled in the dark, disorientating confines of the bivvy bag to locate and switch it off. 5.30am, still dark. I dozed on for another 45 minutes and the beginnings of grey dawn, then wrenched myself out of my warm cocoon and into wet socks, neoprene socks and trail shoes. After a hurried miso soup and a buttery (fusion cuisine, backpacking style!) I climbed towards Stob a'Choin. Venus and a sliver of moon hung just above the shoulder to my right as I set off. Soon I was amongst the complex gullies, crags and streams, picking a way through, using hands sometimes. I emerged near the summit as the sun rose out of a bank of low cloud to the east and painted the hilltops. The Crianlarich hills were close and huge and brutal-looking to the north, Stob Binnein especially impressive, drawing up its bulk from the glen floor, above broad skirts seamed with gullies and crusted with outcrops, to a fine complex of sweeping ridges. Cloud came and went from its summit.

I touched the tiny cairn then wavered for a few minutes wondering whether I should visit another little top a couple of hundred metres north west 'just in case'. But in the end I turned and jogged downhill; I'd told Mick I'd be back by 8 and we had a boat to catch later on.

The day's next act was the hardest, especially for bodies already tired by a day and a half of trackless bog and moorland. We picked up where we left off, descending to the glen where the tightly meandering Allt a'Choin flowed generally south to Loch Katrine. The glen floor was sodden and vegetated, trackless of course. We started to get a feel for reading the vegetation, where we might expect ankle-sucking bog or drier going.

I felt ropy with fatigue and hunger after my dawn climb. Deer fences closed in on either side of the burn sheltering trees recently planted as part of the Great Trossachs Forest project. I made an ill-thought-through attempt to cross the burn over a natural weir of slimy boulders towards a gate in the fence on the far side and nearly fell in. I had enough insight to realise I wasn't thinking straight, and drew back. In the end, the two deer fences never met and we made it down to the road by Loch Katrine following a well established deer trod through the bracken and head-high birch scrub, clearly a well-used corridor for the animals to reach the shelter of the loch side woods from the high ground..

The deer fences were controversial when they first went up to protect the new plantings. It seems the migratory paths from upland to valley shelter were disrupted, trapping the animals above the treeline in harsh weather. It's hard to know what the answer is. Perhaps it's an example of failing to tackle a problem head on, a modern tendency to avoid difficult choices and favour complex workarounds with unintended (and in this case, arguably cruel) consequences - to try to change everything while changing nothing. Think electric cars or biofuels or geoengineering to combat climate change. Would a serious reduction in deer numbers via culling to a level where deer fences are not needed, actually be more humane? One thing is for sure, deer belong in the Highlands, they're magnificent animals well attuned to their environment. Watch a red deer take minutes to cross the hillside you've spent the best part of an hour toiling across. I hope very much we don't start to think of red deer as 'vermin', rats with antlers.

A tarmac road runs along the north shore of Loch Katrine and round to Stronachlachar on the south side. It was a shock to be back suddenly in daytripper land straight from some of the loneliest hill country in the southern Highlands. A steady trickle of bikes passed us as we plodded along in silence, both wrapped up in fatigue. We passed the old Clan Gregor burial ground on a promontary in the loch, and Glengyle House, birthplace of Rob Roy. There used to be a village in upper Glen Gyle. Now the Beauly-Denny pylons march down the glen, and the massive service road. It must have been a lovely place once, where the glen tapers away to the horizon from the head of the loch. Now it's industrial and off-putting.

The original plan had been to strike uphill to Beinn a'Choin from here, taking a direct cross-country route to Loch Lomond, but more deer fences stretched across the hillside. That was enough to put us off. We walked on to Stronachlachar for lunch by the pier where the steamer calls in the summer. A dustbin lorry pulled up containing two very bored refuse collectors spending the day travelling long distances along narrow roads to empty a small number of bins. We could relax a bit now as we only had a few easy miles to Inversnaid. After a leisurely lunch and much refreshed we picked up the Great Trossachs Path heading west above Loch Arklet. This section was a surprising gem. The trail follows the line of the old military road to Inversnaid Garrison, well above the public road, through patchy woods. The Arrochar Alps filled the view ahead. On the right, the slopes up to Beinn a'Choin are open and accessible here, noted for next time.

Before long we were winding through the oakwoods down to Loch Lomond, and I was thinking how great it was to see and approach it from a new angle, and be reminded that there's a good reason for all the fuss and popularity. We fell off the teetotal wagon with pints outside the Inversnaid Hotel, waiting for the waterbus to Tarbet. We'd made it easy on ourselves on this trip, and also difficult. It was a hard one to sum up. "Here's to another... victory" said Mick hesitatingly as we clinked pints. When you link up mountains that shouldn't be linked up, strange and wonderful things happen.

Comments

Post a Comment